Royal Variations

After a five-year absence, the Royal Ballet is in town again, in time for its 75th anniversary. On Tuesday night, the Royals presented a program of four ballets created in various times by the company’s own choreographers: La Valse and Enigma Variations by Frederick Ashton (The Royal Ballet’s founding choreographer), Gloria by Kenneth MacMillan (Ashton’s successor as the company’s Artistic Director), and Tanglewood by Alastair Marriott (the company’s dancer and aspiring choreographer).

The name of Frederick Ashton is integral to the history of the Royal Ballet. He sculpted British classical dance and created some of the most popular ballets that built the company’s name, so it wasn’t surprising to see two of his works on the program’s menu.

Created in 1958 for the La Scala Ballet, Ashton’s La Valse is a glamorous dance and perfect curtain-opener. “Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds slowly scatter: one sees... an immense ball room filled with a whirling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated,” wrote Maurice Ravel about La Valse. And this is how Ashton’s ballet begins in a ball room, decorated with gorgeous blue multiple-layered drapes and crystal chandeliers. Men in black tail coats, women in dazzling evening gowns and white gloves are indulging in a waltz. Ravel’s music sets an exuberant and at the same time ominous mood for the dance. The Royal Ballet had it all: stunning decorations, beautiful costumes, and a great band (the Washington National Opera Orchestra). Unfortunately, a lack of unison movements of the corps de ballet made the dance less effective and visually appealing. It was quite disappointing to see dancers not being able to demonstrate synchronized arm- and footwork when the music itself serves as a perfect metronome. The male corps looked stronger, while ballerinas reminded of debutantes on their first ball. As a result, the thrill and excitement of the dance were conveyed mainly by the orchestra.

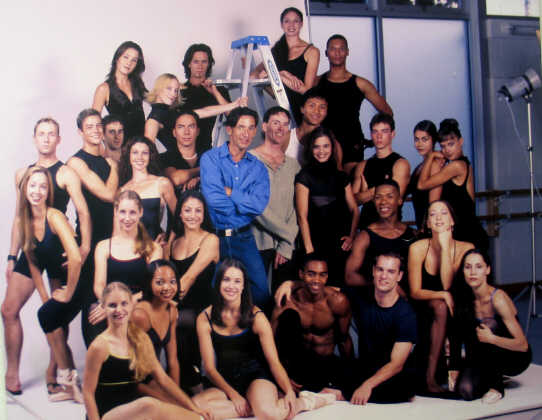

The urgent and somber sounds of a solo violin opened the second ballet of the program, Tanglewood. Choreographed to the violin concerto of the American composer Ned Rorem (six movements conceived as songs without words) it’s dance driven by music, not plot. Slick gray and white costumes, striking abstract backdrops, and thoughtfully designed lighting created a romantic and dreamy atmosphere. Amid a sense of purposelessness, it was enjoyable to watch mainly because of a superb performance given by soloists: Martin Harvey, Leanne Benjamin, and Marianela Nunez.

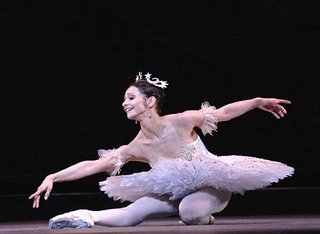

Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations, subtitled My Friends Pictured Within, gave inspiration and title to the second Ashton work of the evening. Fourteen variations created by the composer in 1899 represent a collection of affectionate musical portraits of his family, friends, and acquaintances. This ballet could be perceived as a photo album of them, with pictures becoming ‘alive’ during each variation. There are monologues, dialogues, and conversations all in the form of dance. It’s a beautifully choreographed and staged work. Christopher Saunders gave a solid performance of Edward Elgar while Zenaida Yanowsky impressed as his faithful wife. Roberta Marquez sparkled as little Dorabella dancing gracefully and joyfully. Sarah Lamb was perfect as Lady Mary Lygon – a mysterious, fairy-like character. Her spectacular love duet with Elgar was full of passion and tenderness. Elegant, nostalgic, humorous, and idyllic, “Enigma” was truly enjoyed and appreciated by the audience.

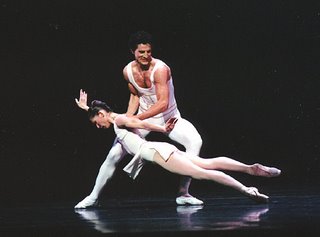

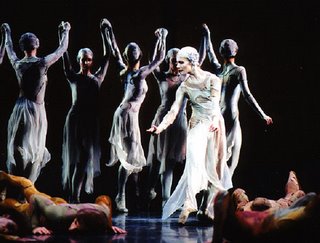

The 1980 MacMillan Gloria was inspired by Vera Brittain’s autobiography Testament of Youth and commemorates and laments the victims of World War I. The ballet is set to Francis Poulenc’s Gloria from his Latin Mass, which was masterfully performed that evening by the WNO orchestra and the Washington Chorus. Alas, the choreography was less profoundly moving. The powerful emotional effect one would expect from such a work was absent. Perhaps, it was too much of a task to relay human pain and suffering caused by a war in a short dance… What made this dance stand out from the entire program was the quality of its cast, especially soloists Alina Cojocaru and Thiago Soares.

Starting June 22nd, the Royal Ballet is presenting their classic revival of Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, which I have previously written on here.